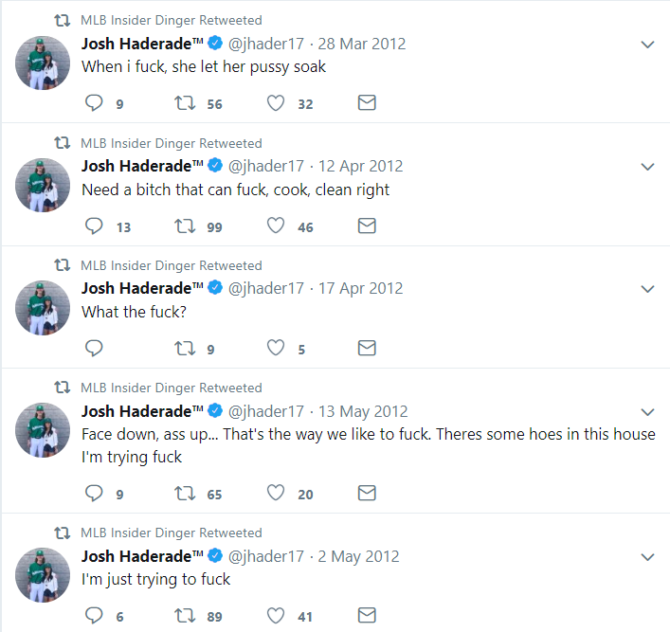

Unless you’ve been playing fantasy baseball and were in need of an undrafted reliever like me, you might not have known who Josh Hader was until the 2018 MLB All-Star Game. Hader’s All-Star selection was a bittersweet honor in more than one way. He allowed three runs in a third of an inning and then discovered after the game that he’d have to complete sensitivity training for racist, sexist and homophobic tweets made at 17.

The tweets were uncovered by Twitter users with too much time on their hands. These investigations into the social media statements of minors are unfair to the public figures who made the statements because minors aren’t entirely responsible for themselves, legally speaking. Journalists seldom quote minors for that very reason. Their parents share responsibility for their words and actions until they’re 18.

While I agree with my colleague, Dan Szczepanek of Grandstand Central, that Hader’s “young and dumb” excuse isn’t good enough, he isn’t solely responsible for the social media statements he made as a minor. His parents share that responsibility, but not in the court of public opinion. It is troubling, however, that just seven years ago and even to this day, racist, sexist and homophobic thoughts are running through the minds of American minors.

On the Foul Play-by-Play podcast, my attorney and I discussed how to remedy the racist, sexist and homophobic sentiment that seems to be growing or at least getting louder in America. Reforming haters is a delicate process not unlike treating addiction. It requires the dedication of the addict first, and an empathetic, supportive community providing evidence consistently contradicting the addict’s former mentality. But hate, like addiction, isn’t curable, only treatable.

“There’s no magic cure, no such thing as a ‘life after hate,’ only a life of fighting not to succumb to it” Wes Enzinna wrote for Mother Jones’s cover story in the July/August issue. Not everyone is as fortunate as Hader was to grow into a man in an environment conducive for avoiding an addiction to hate.

Without social and familial support and a safe environment facilitating the formation of relationships between diverse groups of people, haters gonna hate. That’s why Barack Obama’s administration added the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing rule to the Fair Housing Act in order to address segregation that persists in public housing. Department of Housing and Human Development Secretary Ben Carson has since suspended enforcement of the rule, resulting in a lawsuit brought by the National Fair Housing Alliance and joined by the state of New York.

Those living in environments that perpetuate hate can also learn something from Hader’s hateful tweets coming back to bite him. Even parents perpetuating hate in the home have their children’s preservation as their top priority, so talking with their children about safe social media usage, similar to the talk about practicing safe sex could result in fewer instances of hate speech online.

If children in the moment are too emotional to consider the effect their words might have on others, perhaps they’ll resist using hate speech over their own interest in self-preservation. Just as images of STDs are used in sex education courses to scare young people into practicing abstinence or safe sex, stories like Hader’s and Roseanne Barr’s might be enough to scare children from publicly expressing hate if their parents explain how imperative it is that their children are employable.

And if Hader’s and Barr’s stories aren’t scary enough, or children don’t understand why they should protect something they don’t yet have, maybe they’ll protect something they do. A fifth of undergraduate college students believe physical force is an acceptable response to “offensive and hurtful statements,” according to a 2017 Brookings Institution survey. So hate speakers have to consider whether they’re prepared to defend themselves, although most instances of violence resulting from hate speech indicate they are, which is why it’s so important that Hader do more than apologize and complete sensitivity training.

Colin Kaepernick didn’t just take a knee during the national anthem. He thoughtfully explained why he took a knee when asked, sought feedback from military personnel as to avoid offending them and backed up his words and actions with his money. Kaepernick has donated a million dollars to organizations working in oppressed communities as of January. Life After Hate, an organization working to reform haters, received a $50,000 donation from Kaepernick. Since Hader doesn’t make millions of dollars, he should donate his time and image to the movement to end hate.

If Hader was willing to take the time to trademark his nickname, “Haderade,”he can take the time to start a nonprofit called Hater Aid, an organization that helps haters stop hating. I’ve started two nonprofit organizations, make a lot less than Hader’s $555,500 annual salary and had no previous training. If he needs some guidance, the National Council of Nonprofits provides all the information he needs.

I would only recommend Hader focus his efforts locally to start. If the standing ovation he received from Brewers fans at Miller Park in his first appearance since the All-Star Game is any indication, he still has the support of Milwaukeeans, at least until he struggles to get MLB hitters out. Regardless of his performance on the field, Milwaukeeans will appreciate Hader focusing his off-field efforts locally, and there’s plenty to be done in Milwaukee.

According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, there are four active hate groups in Milwaukee alone and nine statewide. So Hater Aid’s initial mission should be to eradicate hate in Milwaukee first, then the state of Wisconsin, and then the region and nation. It’s also cheaper and easier to start and run a locally-focused nonprofit than one with a state or national focus.

With a modest, tax-deductible donation from Hader to found Hater Aid and a bit of paperwork to incorporate the organization and acquire a tax exemption, Hater Aid could be up and running before the end of the baseball season. MLB and the Brewers’ public relations department would love for Hader to dedicate some free time to meeting with former haters in the Milwaukee area willing to share how they managed to stop hating. If interested, they could serve as Hader’s Hater Aiders, a group of volunteers, interns and paid staff to run the day-to-day operations of Hater Aid, including a 24-hour, hater hotline for haters who want to stop hating but aren’t sure how.

If Hader were to take these steps, his national image wouldn’t just be repaired — it’d be more valuable than it was before the tweets were uncovered. It never hurts to be a role model and a community contributor in contract negotiations, either. By the time Hader’s eligible for free agency in 2024, Hader’s Hater Aiders will have helped haters stop hating throughout Milwaukee and, perhaps, the state of Wisconsin if not the entire country.

Hader might never have been addicted to hate, but that doesn’t mean he can’t be the face of a movement to end hate. He should embrace and take advantage of this opportunity if he wants to earn a standing ovation from anyone other than Brewers’ fans.